DUBAI: On March 11, 2020, just a matter of months after it first emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan, outbreaks of the novel coronavirus were reported from multiple continents — marking the start of an unprecedented health emergency and an abrupt change in daily habits.

After the World Health Organization (WHO) decision to raise its alert from a scattering of localized epidemics to a full-blown pandemic, governments in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) area were quick to respond.

Mandatory nationwide closures were put in place, schools and workplaces emptied, front-line workers mobilized and households ordered to stay home. Few could remember a time of such disruption or ever seeing their streets so empty.

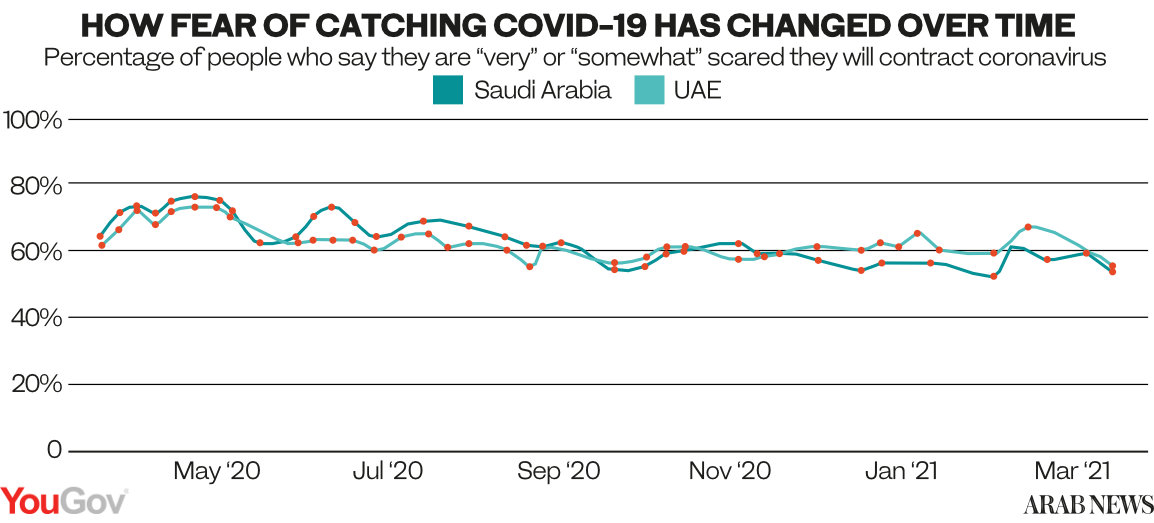

Data collected by British polling agency YouGov found that in April 2020, at the outset of the pandemic, some 75 percent of respondents across Saudi Arabia and the UAE felt “somewhat” or “very scared” of contracting the virus. This fear has generally fallen as the pandemic has worn on.

To curb the spread of COVID-19, governments placed much of the onus on the general public to abide by new personal hygiene and social distancing guidelines.

In the same YouGov poll, 78 percent of Saudi and UAE respondents said they had improved their personal hygiene (frequently washing their hands and using hand sanitizer), while 80 percent said they had avoided public places and 70 percent said they had started wearing face masks in public.

COVID-19 spreads primarily through contact with infected individuals when airborne particles are expelled through coughing and sneezing. It can also be spread by touching contaminated surfaces and transferring particles to the eyes, nose and mouth.

A Saudi police officer inspects a motorist's permit to travel during the lockdown in the Kingdom in April 2020 to fight the spread of COVID-19. (SPA file photo)

The combination of lockdown measures and ubiquitous public health messages has had a profound effect on people’s daily lives, running the gamut from how they work and study to how they travel and socialize.

It has also highlighted the significant role that widespread community uptake of hygiene and social distancing rules can play in successfully containing outbreaks.

During the first six months of the pandemic, YouGov data showed rates of mask wearing were high in the GCC. Some 80 percent of UAE respondents and 69 percent of Saudi respondents said they were consistently wearing face masks during this period.

Throughout the pandemic, at-risk groups, including the elderly and those with underlying health conditions, have been urged to be extra vigilant. In August 2020, 80 percent of Saudi respondents over the age of 45 reported having avoided public places, whereas just 58 percent of 18-24-year-old Saudis said they took the same precautions.

In the same month in the UAE, 81 percent of people aged over 45 reported wearing a face mask in public, while just 66 percent of 18-24 year olds said they were complying with the mandatory mask rule.

Although men and women are equally susceptible to catching coronavirus, medical data suggests men are more likely to suffer from severe symptoms and ultimately die from the disease.

In August 2020, four out of every five Saudi respondents over the age of 45 reported having avoided public places. (Reuters file photo)

And yet, despite WHO advice to the contrary, YouGov data found that male Saudi and UAE residents were less likely to improve their personal hygiene, less likely to wear face masks, less likely to avoid crowded places and less likely to avoid touching potentially contaminated surfaces.

Since the pandemic began, nearly 142 million people have been infected worldwide and more than 3 million have died. The UAE has seen about 500,000 COVID-19 cases, while Saudi Arabia’s total is approaching the 405,000 mark.

Compared with many European states, where governments were slower to react to the pandemic, the outbreak in the GCC has been relatively mild, with a much lower death rate. But even here, as vaccines are rolled out and restrictions are gradually eased, things feel a long way from normal.

ALSO READ:

• Middle East, global attitudes reshaped by coronavirus pandemic

• Study finds growing acceptance in the Middle East of coronavirus ‘new normal’

“What’s happening to us may seem to so many people to be alien and unnatural, but plagues are not new to our species — they’re just new to us,” writes social epidemiologist Dr. Nicholas Christakis in his book “Apollo’s arrow: The profound and enduring impact of coronavirus on the way we live.”

And just like the great epidemics of the past, writes Christakis, the COVID-19 pandemic will eventually pass, bringing with it a brighter period in which people seek out long-denied social interactions.

The Yale professor even predicts a second “roaring 20s” similar to the decade of prosperity and cultural resurgence that followed the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918.

But in order for this to happen, people must be safe — and feel safe. Annual vaccinations, improved treatments and vaccine passports are all possible tools to get societies and economies back on track.

Until then, the behavior of those least at risk will continue to impact those most at risk. Therefore, getting “back to normal” will depend not only on medical science, but on the actions of the community as a whole.

Without a widespread uptake of vaccines and containment measures, the virus will enjoy a stronger foothold and a greater chance of mutating, allowing it to become more transmissible and its symptoms more severe.

“When a virus is widely circulating in a population and causing many infections, the likelihood of the virus mutating increases,” according to the WHO’s “Vaccine Explained” series. “The more opportunities a virus has to spread, the more it replicates — and the more opportunities it has to undergo changes.”

INNUMBERS

83% Saudi respondents who believe the pandemic situation is improving.

14% UAE respondents who believe the pandemic situation is getting worse.

70% Saudi and UAE respondents who say they will continue avoiding crowded places.

Source: YouGov COVID-19 Public Monitor, March 2021

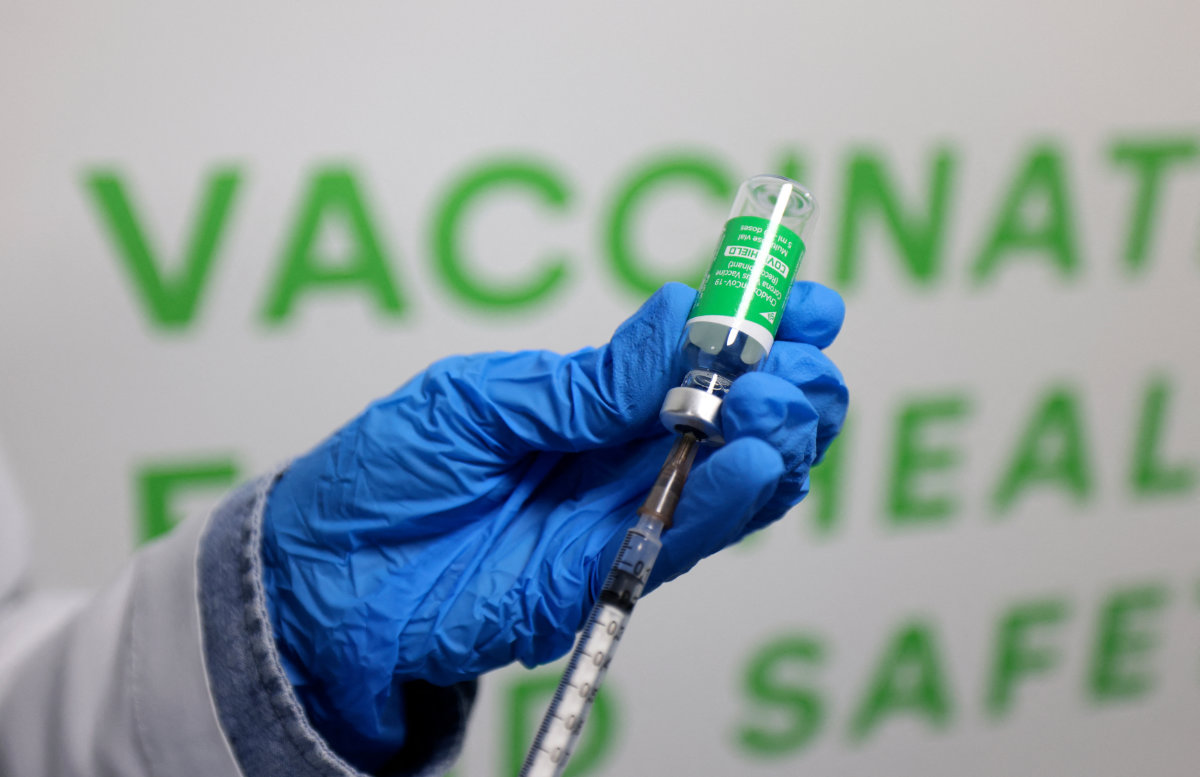

A major factor in uptake is the trustworthiness of the vaccines on offer.

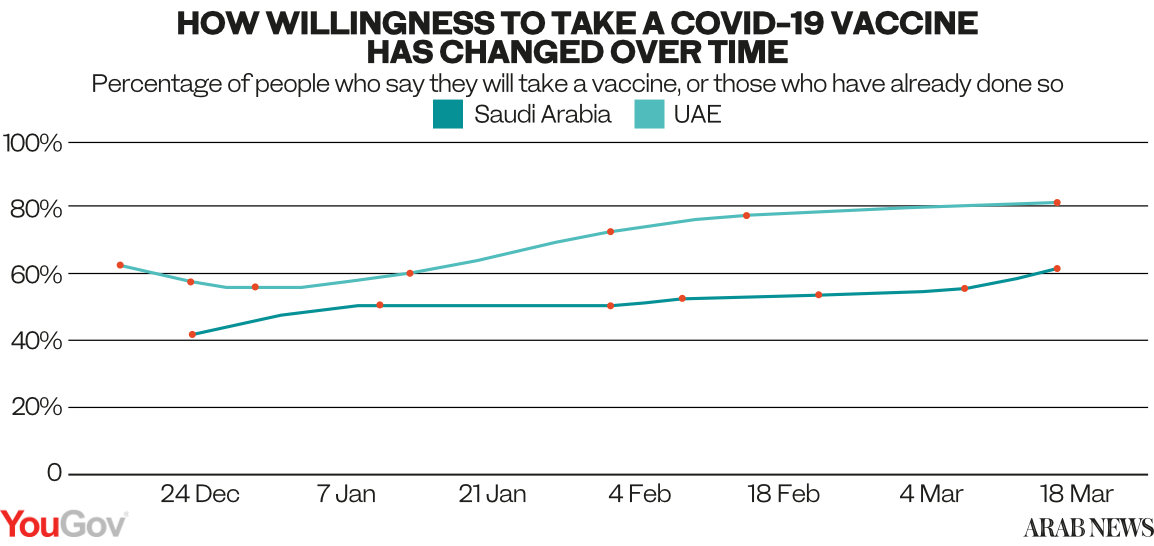

In early December last year, the UAE became one of the first countries to approve the Chinese-made Sinopharm vaccine for emergency use. YouGov’s polling data at the end of that month found that just 56 percent of UAE respondents felt comfortable taking the vaccine or had already done so. In Saudi Arabia, that figure was only 42 percent.

An Emirati man gets vaccinated against COVID-19 at al-Barsha Health Centre in Dubai on December 24, 2020. (AFP file photo)

Since the national vaccination program was launched in Saudi Arabia, more than 2 million doses have been administered at 500 centers across the Kingdom. In the UAE, which has one of the highest vaccination rates per head of the population in the world, more than 10 million have been administered.

Since the December 2020 poll, confidence in the safety and efficacy of the new crop of COVID-19 vaccines has grown. Data from the YouGov COVID-19 Public Monitor in March 2021 showed an increase in willingness to take the vaccine by 20 percent of respondents in Saudi Arabia and 26 percent in the UAE.

Now the vast majority of respondents in the UAE (82 percent) and in Saudi Arabia (62 percent) say that they have either received a vaccine, or are willing to take one.

In other findings, 83 percent of Saudi respondents believe the pandemic situation is improving; only 14 percent UAE respondents believe the pandemic situation is getting worse, while but 70 percent of Saudi and UAE respondents intend to continue avoiding crowded places.

None of this is surprising given that scientists still have a lot to learn about COVID-19, its mutations, spread patterns, long-term symptoms and its ability to outmaneuver the vaccines and treatments doctors throw at it.

Mask wearing, hand sanitizing and social distancing might therefore be requisite behaviors for some time yet to come.